This story originally appeared on the Jimmy Fund website. For more information on the Jimmy Fund, visit jimmyfund.org.

In 1992, I was diagnosed with stage 3 multiple myeloma, a cancer of the bone marrow, and I was told that I would live two to three years with treatment, or nine months without it. I was 43.

That was 18 years ago. Today, my wife Kathleen and I have been married for 39 years. We have two grown sons, Robert and James, and three grandchildren: Jillian, Wade and the fourth generation James Bond. I recently retired from full-time work as a CPA. I rode my bicycle 328 miles across Ohio for the past three summers, and am training to do so again this July.

I am living with my cancer while receiving care at Dana-Farber as well as from University Hospital’s (UH) Ireland Cancer Center in Cleveland, close to my home. My care teams at both centers work together to coordinate my care, which to me illustrates the value of teamwork.

Before my diagnosis, I’d had some soreness in my lower back, and Kathleen thought I looked pale and haggard despite my general sense of good health.

Test results showed I had a mysterious lesion on my spine, broken ribs from sneezing, and a skull that looked like Swiss cheese — all caused by multiple myeloma, an incurable form of cancer with very few treatment options.

Over the next decade I received a variety of chemotherapy drugs and three stem cell transplants at UH, under the care of Dr. Hillard Lazarus. After the third transplant, my disease was gaining ground. By 2002, it was raging.

My kidneys were failing, I was unable to eat solid foods, I had fevers reaching 105 degrees and I needed blood transfusions to stay alive. I was out of conventional options, and things looked bleak. I had already lost my parents and youngest sister to cancer, and I thought it would kill me, too.

Consultations with Dr. Phil Greipp of the Mayo Clinic led us to a promising clinical trial for a new drug called PS341, now known as Velcade. We learned that Dana-Farber was enrolling patients, so I called Dr. Paul Richardson, the clinical investigator.

He returned my call right away and asked two questions: “Can you move to Boston for nine months?” and “How soon can you get here?”

My answers were “Yes” and “Tomorrow morning.”

By the time we arrived in Boston, I was critically ill. From our hotel room, Kathleen talked with Dr. Ken Anderson, who was on call at Dana-Farber. He told her how to help me get through the night and said, coincidentally, I was the seventh patient to enroll in the trial with a study number of 007. He said, “Mrs. Bond, I think that’s good karma.”

At our first appointment, a volunteer named Sandy Cunningham stopped by to chat. He asked where we planned to live for the next nine months. When we told him we were looking for an apartment, he said, “Use our home for the summer. We’re going to be out of town on Cape Cod.” We settled gratefully into the Cunninghams’ suburban Boston home. More good karma?

Within two weeks after I started the clinical trial, under the care of Dr. Richardson and his superb research nurse, Deborah Doss, the dangerously high-level protein in my blood was practically gone, the swelling in my legs was down, I could eat again and the fever had disappeared. I had almost no side effects and continued to work full-time from Boston.

When the nine months ended I went back to Cleveland, where I enjoyed complete remission for a year. During this period, Velcade was approved by the FDA.

Eventually, my protein levels began rising again, but not as aggressively as before. I returned to Dana-Farber in 2004 and entered another clinical trial led by Dr. Richardson that was studying the activity of lenalidomide. The drug, later called Revlimid and approved by the FDA, produced another remission. I am still taking it, with minimal side effects.

Even though I enjoy an active life, I do have some long-term effects from my treatments. The transplants weren’t easy. I still have slight graft vs. host disease, which includes mouth sores, slightly dry eyes, and occasional mild gastro-intestinal difficulties.

The steroids I took caused a loss of blood to one of my hip bones, so I needed a hip replacement in 2005. Three full-body radiation treatments caused cataracts in both eyes, and I have muscle cramps, slight neuropathy in my fingers and toes, and my thyroid has permanently failed.

Throughout my care, I continued to work full-time — either in our Cleveland office, our Boston office, from home, or from my laptop in various hotels and hospitals. The support and compassion of my colleagues at work were invaluable to me and my family. In retirement, I volunteer to help other families affected by cancer and stay active.

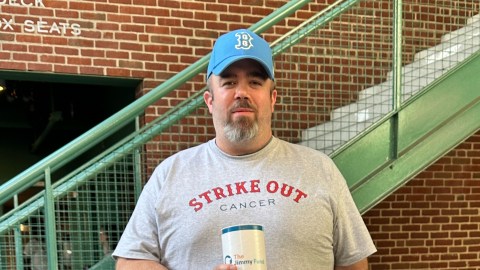

In addition, for the past three summers I’ve bicycled from Cleveland to Cincinnati in the Pan Ohio Hope Ride, a four-day bicycle tour to raise awareness for the American Cancer Society’s Hope Lodges, where cancer patients can stay for free while being treated at centers away from home. I will ride again this summer.

Kathleen developed this event in 2007, and she has been very involved with the Society, serving on its national board of directors as well as the Ohio and Cleveland boards and the Hope Lodge board in Cleveland.

I am delighted to say that Boston now has an ACS Hope Lodge, only a mile from Dana-Farber.

Family and friends were critical to our success, as well as the doctors, nurses, hospital staff and lab technicians involved in our care and the research companies in this field. We realize how fortunate we are. One takeaway from our story is that in the face of adversity, the right attitude and purpose can make a tremendous difference.

The photo is from Pan Ohio Hope Ride Facebook page.